Jan. 3, 2022 -- Ten-year-old Josiah Oyeleye is a very different child than he was 3 years ago, according to his mother, Ife. While his peers had seemingly boundless energy, Josiah would tire quickly and needed frequent naps.

Intense fatigue is just one of the many debilitating symptoms of sickle cell disease, a hereditary blood disorder that Josiah was diagnosed with at 3 weeks old.

But Josiah turned a corner when he enrolled in a clinical trial for Oxbryta, a treatment for sickle cell disease that was just approved for children ages 4-11. The drug, which the FDA approved in December, treats the root cause of the disease rather than the symptoms, filling a void for the chronically underserved patient population, doctors say.

“Just doing basic things like playing, he’d need to take breaks,” said Ife, who lives in the Atlanta area. “Now, that is gone, he’s stopped taking naps, and it's very obvious that he is just like his friends, his peers. We're truly grateful.”

Josiah’s sister, Micaiah, and father, Fola, also live with the disease.

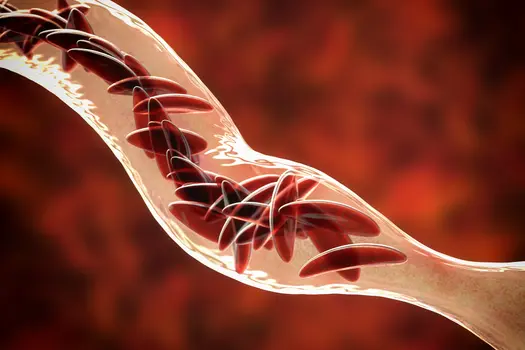

Sickle cell disease is marked by flawed hemoglobin, or the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen to the tissues of the body. This changes the shape and texture of red blood cells.

The cells, which are normally smooth and disc-shaped, become crescent-shaped, resembling a sickle. They are also stiff and sticky, causing them to clump together.

This can cause a wide range of complications, including organ damage, stroke, and chronic pain.

It disproportionally affects people of color. The disease occurs in about 1 out of every 365 Black or African-American births, and about 1 out of every 16,300 Hispanic American births.

The expanded use for Oxbryta, made by San Francisco-based pharmaceutical company Global Blood Therapeutics, represents a “Renaissance age for sickle cell disease,” says Clark Brown, MD, a pediatric hematologist at Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta and primary investigator for the Oxbryta clinical trials.

“There is a huge unmet need in this patient population,” he says. “Now there is a greater awareness about the need and better advocacy for the patient population.”

Racial bias has hampered sickle cell progress for years, according to researchers, leading to scarce pain treatment and lack of knowledge among health care professionals. Sickle cell patients at one hospital waited 60% longer to get pain medication than other patients who reported less severe pain and were triaged into a less serious category. According to a 2015 survey, only 20% of family doctors said they felt comfortable treating sickle cell disease.

There are few treatments for the disease, the most common being the drug hydroxyurea. But it was first used as a cancer treatment, and many doctors are hesitant to prescribe it due to safety concerns, Brown says. It can reduce the number of white blood cells and require frequent blood tests, while Oxbryta’s safety profile is much milder, as the drug sometimes causes a rash or upset stomach.

Brown says children with the disease are at risk of having life-threatening complications as early as 6 months after birth.

“Early treatment is essential,” he says. “This is expected to slow the disease progression.”

Oxbryta holds the hemoglobin in a particular shape that prevents sickle cells from stacking, preventing complications like organ damage and pain, says Kim Smith-Whitley, MD, head of research and development for Global Blood Therapeutics and a pediatric hematologist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

“The stacking can lead to changes in lungs, hearts, kidneys, that can impact them long-term,” she says. “Their brains are not getting enough oxygen in a quarter of them by 5 years of age.”

While Oxbryta for children 12 and over comes in a tablet that can be swallowed, the newly approved medication is a tablet that dissolves in liquid. Both are available to children as young as 4.

Researchers are looking into the medication’s use for children even younger than 4, down to 6 months old, Smith-Whitley says.

“People with sickle cell die 30 years younger than peers,” she says. “Now we have another medication we can use to address the complications of sickle cell disease in younger children and the first medication directly addressing the underlying cause.”